Accelerate?: Serial Experiments Research Unit, Part 1

Meditation—Jungle-ist cyberpunks and the Marxian origins of acceleration

§20 — Since the late 18th century, the contour of the thing-in-itself has been diagonally crafted to an ever-unprecedented degree of refinement, and yet, still, that is what it is, and nothing else. The boundary of the unknown, and unknowable, is itself the object of an increasingly exact cartography. Setting and re-setting this limit is the original and eternal meaning of critique. Only through diagonal method is it realized.

[…]

§50 — Within 20th century philosophy, the combined work of Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari has been an especially self-conscious site of diagonal production. This is most schematically evident in its critique of structuralism, which draws the diagonalization matrix of form-substance / expression-content with impeccable classicism. In this case, the alignment of form and expression, substance and content, is the relevant order of resonance or redundancy. There is indeed a ‘poststructuralist’ disruption delivered by Deleuze & Guattari, and it is exemplified by the twin pseudo-paradoxes substances of expression and forms of content.

— Nick Land, Zerophilosophy, Note on Diagonal Method

It is at the level of flows, the monetary flows included, and not at the level of ideology, that the integration of desire is achieved. So what is the solution? Which is the revolutionary path? Psychoanalysis is of little help, entertaining as it does the most intimate of relations with money, and recording—while refusing to recognize it— an entire system of economic-monetary dependences at the heart of the desire of every subject it treats. Psychoanalysis constitutes for its part a gigantic enterprise of absorption of surplus value. But which is the revolutionary path? Is there one?—To withdraw from the world market, as Samir Amin advises Third World countries to do, in a curious revival of the fascist “economic solution”? Or might it be to go in the opposite direction? To go still further, that is, in the movement of the market, of decoding and deterritorialization? For perhaps the flows are not yet deterritorialized enough, not decoded enough, from the viewpoint of a theory and a practice of a highly schizophrenic character. Not to withdraw from the process, but to go further, to “accelerate the process,” as Nietzsche put it: in this matter, the truth is that we haven’t seen anything yet.

— Deleuze and Guattari, Anti-Oedipus

Quoted by Nick Land in: A Quick and Dirty Introduction to Accelerationism

The impersonal is apolitical.

We might think a more nihilist aesthetic which seeks not merely to foreground the processes of postmodern audio-necromancy, but rather to accelerate the system to its ultimate demise, to speed up the rate of fashion-flux to a point of irredeemable collapse.

— Alex Williams, Splintering Bone Ashes blog (defunct), quoted in Xenogothic (2021)

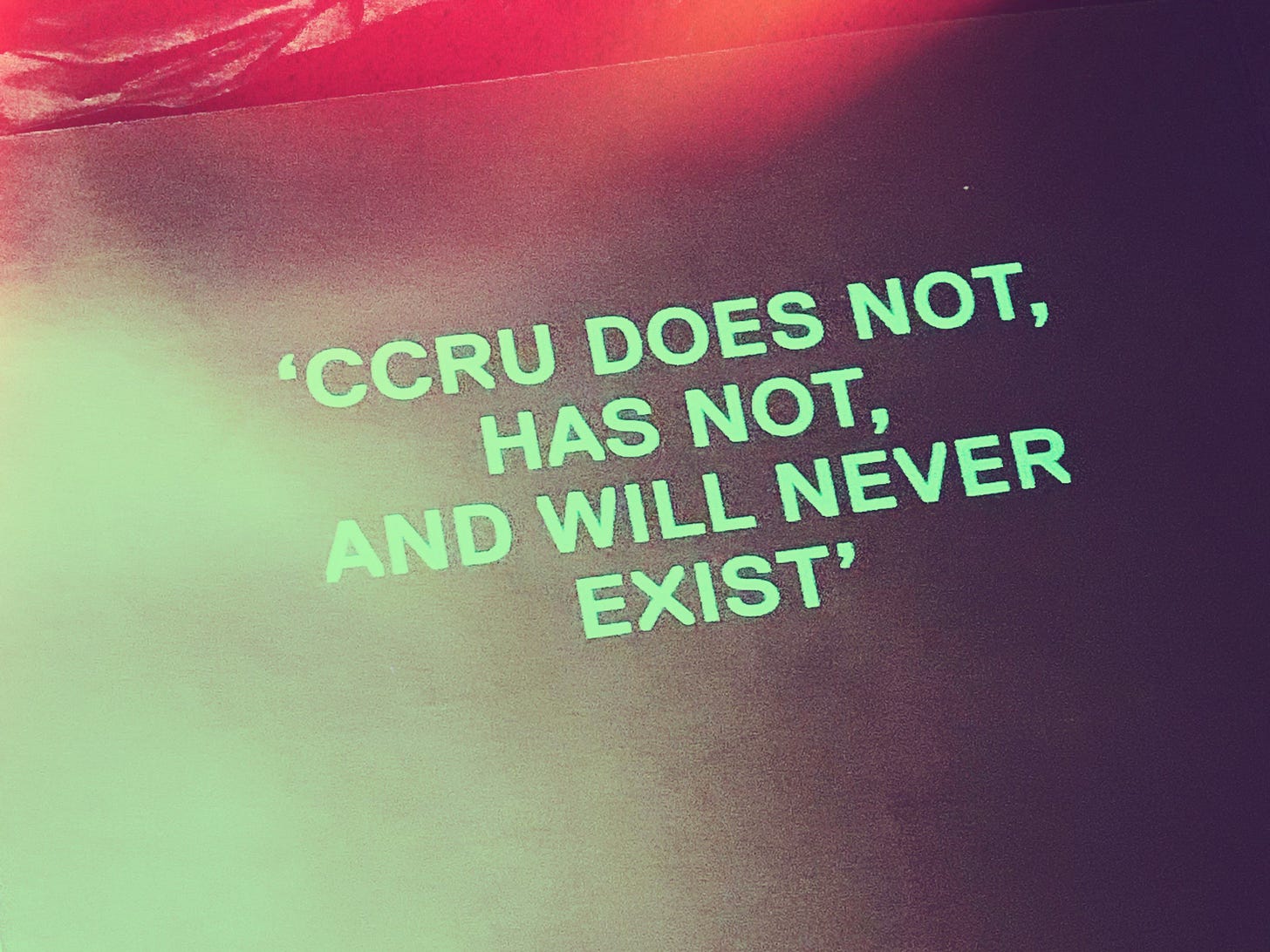

Meditation — Or: This Intro Does Not, Has Not, and Will Never Exist

These past months I’ve been on a quest without a signifier.1 The future is difficult, unknown even to the angels.2 And colliding with the future, also hidden from angelic view, is the human soul3. The future is the impassable ceiling of our aspirations and fears, the soul their container.

A western philosophical trope compresses claims on human nature through a Latin binomial formula: the prefix homo followed by some differentiating suffix—homo sapiens, homo sexualis, homo economicus, etc. This formula might be seen as symptomatic of the mad tension of the collision of social forces in capitalism. But even in another frame, try as they might, the terms never form a unity. With each set of newborn twins. the future will have devoured the pair before they can get their eyes open.4

The tangible public profile around the topic of acceleration(ism) suggests that we are in a heightened moment of collectively questioning the nature of human trajectory and purpose. This is doubly unsurprising given the technologically-driven, mass-sensitizing environment that informs so much of our social, political, and broadly philosophical discourses. Technology-as-media is an extension of human intention that turns back on its human subjects. It propels us into a future of its making, almost in knowing parody of Scripture:

Do not let your heart be distressed; as you have faith in God, have faith in me. There are many dwelling-places in my Father’s house; otherwise, should I have said to you, I am going away to prepare a home for you?

— John 14:1-3 (Knox translation)5

The specter of the Network haunts the ground of our unvoiced questions as much as it forms the ground of those we are already asking. All this is to suggest that—if only in small ways—we are beginning to map its course, guided by the observation that human minds and bodies, and therefore lives, bear the thoughts and experiences that inform the evolution of this information space called the Internet, which has very recently entered its 35th year. It is with this very practical, human concern that I proceed with a largely speculative exercise.

Jungle-ist Cyberpunks and some Marxian Origins of Acceleration

The value of a multidisciplinary approach to a critical examination of techno-capital and its future has poignant champions in the work of the once Warwick University-based group that claimed—with evident cheek—not to exist. Yet despite having never existed, the Cybernetic Cultural Research Unit (Ccru) lives on in the minds and machines of the present—almost as a performative, manifold iteration of its ideas (see: hyperstition). Their questions of the early Internet age, it seems, are our questions of the present and future.

The whole problem or broad idea of singularity is only as fascinating and edifying as it is challenging to ontology. A popular frame these days treats singularity as some kind of destination, i.e., it’s a teleological marker, and therefore necessarily bound up in metaphysics (whether we like it or not).

In an interview from the 90s, Ccru founding member, Nick Land describes the flattening effects of net technology on society.

There is a very similar pattern that you find in the structure of societies, in the structure of companies, and in the structure of computers, and all three are moving in the same direction, that is, away from a top-down structure of a central command system, giving the system instructions on how to behave, towards a system that is parallel, that is flat, which is a web, in which change moves from the bottom up... and this is going to happen across all institutions and technical devices, it's the way they work.

Contemporary societies are built as machines, as part of machines, and so they reveal themselves machinically. But to analyze the social on machinic, cybernetic lines, demands questions about the limits of such thought.

We exist within a complex system of tightly-woven of relationships that reproduces itself in peculiar ways: binding the soft, machinic-resistant features of the human psyche to the hard, machinic features of networked information. What makes these bonds possible? what do they look like? This compression and interconnectedness of the hard and soft gestures to two oft-competing concepts in the western philosophical mind: unity and simplicity—the one and the many. Another word draws out the relationship more forcefully: singularity.

It is not the consciousness of men that determines their existence, but, on the contrary, their social existence determines their consciousness.

Journey to Singularity

The whole problem or broad idea of singularity6 is only as fascinating and edifying as it is challenging to ontology. A popular frame these days treats singularity as some kind of destination, i.e., it’s a teleological marker, and therefore necessarily bound up in metaphysics (whether we like it or not). It then becomes a serious project of describing this destination—how will we know when we’ve gotten there? One angle on this question, while not offering a precise description of singularity, at least locates our arrival along the path of acceleration: singularity is the result of a process of material evolution, one given special prominence in capitalism.

We see this relationship between capital and acceleration in such passages as these, from the Communist Manifesto (1848)7:

In place of the old local and national seclusion and self-sufficiency, we have intercourse in every direction, universal inter-dependence of nations. And as in material, so also in intellectual production. The intellectual creations of individual nations become common property.

[…]

The bourgeoisie, by the rapid improvement of all instruments of production, by the immensely facilitated means of communication, draws all… nations into civilisation. […] It compels all nations… to adopt the bourgeois mode of production; it compels them to introduce what it calls civilisation into their midst.

Marx appeals to a pattern of social mobilization caused by and necessarily contributing to capital production. Notice, however, that even in Marx’s time—from Marx himself—we are given a view of social mobilization under capital that includes intellectual production, and that ties this production to the “immensely facilitated means of communication.”8

If we cannot say that man is a system, it may be enough to say that man is like a system (and unlike).

Before moving on, it may help to round out the Marxian context by reminding ourselves of Marx’s materialism as it bears upon the connection between material relations and the formation of social consciousness. In the Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy (1859), Marx writes:

The sum total of these relations of production constitutes the economic structure of society—the real foundation, on which rise legal and political superstructures and to which correspond definite forms of social consciousness. The mode of production in material life determines the general character of the social, political and spiritual processes of life. It is not the consciousness of men that determines their existence, but, on the contrary, their social existence determines their consciousness.

It is this question of the social determination of consciousness that I am primarily concerned with. That is, I find that the Marxian trajectory’s branching into modern psychology via psychoanalysis continues to invite thoughtful attention. Edmund Berger, in conversation with the Farm Podcast, anchors this trajectory from Marx to the mid-20th century concerns about new media and the mediating effects of the image.9

To paraphrase Berger:

Marx: All social relations are mediated as economic relations.

Situationism: All social relations are mediated as imagistic relations.10

If we consider mediation-by-images in a sufficiently broad sense so as to include the internal imagery of the mind and its causes, we might begin to trace the connections between the internal space of the mind, and the external space of social information. We might pose such questions as:

Where and how do the two meet?

What structures explain their relationship?

Are such structures even sufficient for this task (of explanation)?

If we include the human within such-and-such structure, then we must be operating on the assumption that the human is somehow a structural being. But this assumes a capacity for structures to somehow describe, even explain, the human. The limits of both terms (structure, human) are unclear. It is also less than clear whether critique, taken as an essentially limit-setting practice (cf. the Land quote earlier in this writing), is sufficient for navigating or resolving this tension: understanding that no account will be complete, we would nonetheless have to determine some reasonable limit—we would need to get the appropriate shape of the structure.

One attempt might divide the otherwise incomprehensible structure into domains of known and unknown quantities. This (I think) is more or less what Kant is doing in his transcendental move: the knowable is what appears (phenomena), the unknowable is what can’t appear (noumena).

It seems that Deleuze and Guattari at least attempt to overcome the tension to the extent that they apply cybernetic reasoning by analogy, so as to accommodate categories that

On one level resist treatment in the terms some self-regulating system

On another level, demand cybernetic treatment.

If we cannot say that man is a system, it may be enough to say that man is like a system (and unlike).

This entry is not fit for a discussion of much of this. For now, I simply want to set up a way toward thinking about the human from the other side of Ccru, beginning with a discussion of desire presented in Deleuze and Guattari’s seminal work, Anti-Oedipus. To approach this, and in the spirit of Anti-Oedipus and Ccru, we will engage in acts of profanity—unspeakable, even if attempted in the form of words.

To be continued.

2023 through the first quarter of 2024

We find this sort of observation as far back as in Aristotle’s Metaphysics:

πάντες ἄνθρωποι τοῦ εἰδέναι ὀρέγονται φύσει

Which gets translated literally as: All men by nature desire to know.

But the sense of extending out of oneself, of stretching out to know, is given in the word ὀρέγονται, ὀρέγω. Liddel-Scott gives:

Text source:

Knox Translation Copyright © 2013 Westminster Diocese

Nihil Obstat. Father Anton Cowan, Censor.

Imprimatur. +Most Rev. Vincent Nichols, Archbishop of Westminster. 8th January 2012.

Re-typeset and published in 2012 by Baronius Press Ltd

Regarding singularity

If only as a note to myself, I’m going to give the punchline away. It seems to me that the word describes many things, all of which can coexist in reality, all of which demand our attention and further inquiry. Among these things, there is singularity considered in the domain of philosophical anthropology, and which points further to the domain of theology.

Singularity in this anthropological-theological register seems to me, for now, to look something like this:

Man, in his formal aspect (intellect/soul, spirit), possesses something like a fundamental structure akin to synderesis (even including it), which conditions him to experience reality in its capacity for the evolution of given elements within it toward some state or end that is describable in terms of synthesis unto resolution.

We are sensitive to this synthesis unto resolution as a feature of reality precisely because it is a feature of reality, unto the eschatological horizon and ultimately beyond it, where this resolution truly completes.

Through this sensitivity, man expresses singularity in various multitudes of analogous forms. As there is an analogy of being we might say that there is also an analogy of singularity.

Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels, The Communist Manifesto (1888 English edition)

In a previous version of this article, I quoted at length. Here is the longer quote:

The need of a constantly expanding market for its products chases the bourgeoisie over the entire surface of the globe. It must nestle everywhere, settle everywhere, establish connexions everywhere.

The bourgeoisie has through its exploitation of the world market given a cosmopolitan character to production and consumption in every country. […] It has drawn from under the feet of industry the national ground on which it stood. [All old-established national industries] are dislodged by new industries, whose introduction becomes a life and death question for all civilised nations, by industries that no longer work up indigenous raw material, but raw material drawn from the remotest zones; industries whose products are consumed, not only at home, but in every quarter of the globe.

In place of the old wants, satisfied by the production of the country, we find new wants, requiring for their satisfaction the products of distant lands and climes. In place of the old local and national seclusion and self-sufficiency, we have intercourse in every direction, universal inter-dependence of nations. And as in material, so also in intellectual production. The intellectual creations of individual nations become common property. National one-sidedness and narrow-mindedness become more and more impossible, and from the numerous national and local literatures, there arises a world literature.

The bourgeoisie, by the rapid improvement of all instruments of production, by the immensely facilitated means of communication, draws all, even the most barbarian, nations into civilisation. […] It compels all nations, on pain of extinction, to adopt the bourgeois mode of production; it compels them to introduce what it calls civilisation into their midst, i.e., to become bourgeois themselves. In one word, it creates a world after its own image.

[…]

The bourgeoisie, during its rule of scarce one hundred years, has created more massive and more colossal productive forces than have all preceding generations together. Subjection of Nature’s forces to man, machinery, application of chemistry to industry and agriculture, steam-navigation, railways, electric telegraphs, clearing of whole continents for cultivation, canalisation of rivers, whole populations conjured out of the ground – what earlier century had even a presentiment that such productive forces slumbered in the lap of social labour?

I am indebted to the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, entry on Globalization:

Karl Marx, in 1848 formulated the first theoretical explanation of the sense of territorial compression that so fascinated his contemporaries. In Marx’s account, the imperatives of capitalist production inevitably drove the bourgeoisie to “nestle everywhere, settle everywhere, and establish connections everywhere.”

The juggernaut of industrial capitalism constituted the most basic source of technologies resulting in the annihilation of space, helping to pave the way for “intercourse in every direction, universal interdependence of nations,” in contrast to a narrow-minded provincialism that had plagued humanity for untold eons (Marx 1848, 476). Despite their ills as instruments of capitalist exploitation, Marx argued, new technologies that increased possibilities for human interaction across borders ultimately represented a progressive force in history. They provided the necessary infrastructure for a cosmopolitan future socialist civilization, while simultaneously functioning in the present as indispensable organizational tools for a working class destined to undertake a revolution no less oblivious to traditional territorial divisions than the system of capitalist exploitation it hoped to dismantle.

Scheuerman, William, "Globalization", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2023 Edition), Edward N. Zalta & Uri Nodelman (eds.), URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2023/entries/globalization/>.

Karl Marx, A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy (1859):

Forms of state could neither be understood by themselves, nor explained by the so-called general progress of the human mind, but that they are rooted in the material conditions of life, which are summed up by Hegel after the fashion of the English and French of the eighteenth century under the name “civic society;” the anatomy of that civic society is to be sought in political economy.

[…]

In the social production which men carry on they enter into definite relations that are indispensable and independent of their will; these relations of production correspond to a definite stage of development of their material powers of production. The sum total of these relations of production constitutes the economic structure of society—the real foundation, on which rise legal and political superstructures and to which correspond definite forms of social consciousness.

The mode of production in material life determines the general character of the social, political and spiritual processes of life. It is not the consciousness of men that determines their existence, but, on the contrary, their social existence determines their consciousness. At a certain stage of their development, the material forces of production in society come in conflict with the existing relations of production, or—what is but a legal expression for the same thing—with the property relations within which they had been at work before. From forms of development of the forces of production these relations turn into their fetters. Then comes the period of social revolution.

Karl Marx, A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy (1859), trans. from the Second German Edition by N. I. Stone

For an excellent discussion of how the above informs Das Kapital (1867), see Sahil Kumar’s lecture for Theory Underground: Das Kapital vol. 1 with Sahil Kumar

Link to relevant Episode of the Farm Podcast:

The spectacle is not a collection of images, but a social relation among people, mediated by images.

Guy Debord, Society of the Spectacle (1967)